Up until this year, Silicon Valley bank (SVB for short) was the 16th largest bank. It grew significantly over the past decade as the preferred bank of high-tech startups, growth that only accelerated during the pandemic as the tech sector boomed. With the huge influx of cash SVB received during this period, came a challenge. They had to figure out where to put it. Unfortunately, the management of the bank chose poorly.

Banks do not keep their all their clients’ cash on hand. Though the government does have some regulation as to a minimum amount they must have for “liquidity” reasons, banks mostly invest money in a portfolio to get some form of income while the cash is unused by depositing clients. This can be equity, mortgages, or other debt vehicles. SVB chose to invest largely in a single type of loan – long term treasuries. In stable interest rate environments, Long term debt is a safe, if low yielding form of investment. But in the wake of Covid, interest rates have been anything but stable.

There is an inverse relationship between rates and bond values. When rates go up the value of bonds go down (and vice versa). AS rates rose over the past three years, it significantly harmed the value of SVB’s mortgage-backed securities portfolio. Job cuts came to the tech sector and SVB’s clients needed much of their cash back from their bank. Short on cash to fulfill these withdrawals, SVB sold their long-term bonds – which had lost value as their rates were set during a lower federal reserve rate period.

They sold a $21 billion bond portfolio, recognizing a $1.75 billion loss. The bank announced they needed to raise capital. This sent their already nervous clients into a frenzy causing a bank run like the one in 1946’s It’s A Wonderful Life.

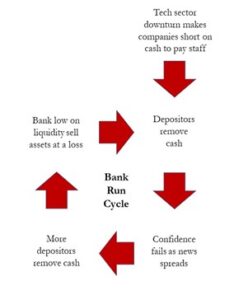

Bank runs are vicious cycles. As a bank must sell off more investments to service clients withdrawing more money, causes the bank to recognize more losses, which panics more clients into withdrawing more money. Without outside intervention, the end of the cycle is insolvency and bank failure. This happened to SVB over two days. The bank collapsed, forcing the government to step in to contain the damage to keep this from harming the entire banking sector. Two days later Signature Bank closed, and the government stepped up to guarantee the money back to those who had money deposited, though they did not protect the shareholders.

SVB was the biggest US lender to collapse since the 2008 global financial crisis and the second largest ever. SVB, while large, only accounted for less than 1% of all banking assets in the US. SVB was collapse is less systematic, in cause, and more a case of incredibly short-sighted investment and risk supervision on part of its managers. Banks currently have much stronger financial buffers than in the past, with capital to absorb losses should they have to take them on their portfolios. Going forward, The government and the FDIC have shown a willingness to protect depositors. Regulations are likely to become stricter, so the ineptitude in the style of SVB’s leadership will come to light sooner. As a sector, this implies a correction for banking, but ultimately a healthy one.